President Trump will order his health secretary to declare the opioid crisis a public health emergency Thursday — but will stop short of declaring a more sweeping state of national emergency, aides said.

WASHINGTON — President Trump will order his health secretary to declare the opioid crisis a public health emergency Thursday — but will stop short of declaring a more sweeping state of national emergency, aides said.

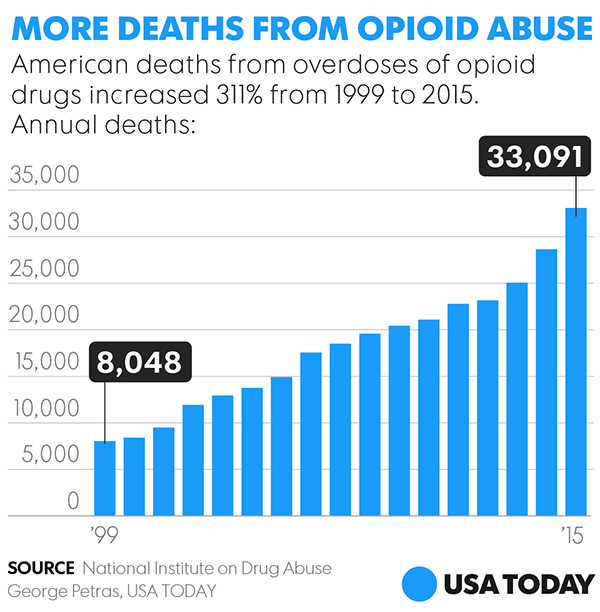

In an address from the White House, Trump will also try to rally the nation to a growing epidemic that claimed 64,000 American lives last year, and will advocate for a sustained national effort to end to the addiction crisis.

“Drug demand and opioid misuse is the crisis next door,” said Kellyanne Conway, a senior counselor to the president, previewing the tone of Trump’s speech Wednesday. “This is no longer someone else’s co-worker, someone else’s community, someone else’s kid. Drug use knows no geographic boundaries or demographic differences.”

To respond to that crisis, Trump will sign a presidential memorandum ordering Acting Secretary of Health and Human Services Eric Hargan to waive regulations and give states more flexibility in how they use federal funds, said four senior officials responsible for crafting the administration’s new opioid policy. The officials previewed the action to USA TODAY on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak ahead of the president’s announcement.

Trump first promised to declare a national emergency to combat the crisis on Aug. 10, and repeated that pledge last week. Speaking to reporters on the south lawn of the White House Wednesday, Trump touted a “big meeting” on opioids, and said a national emergency “gives us power to do things that you can’t do right now.”

But there’s a legal distinction between a public health emergency, which the secretary of Health can declare under the Public Health Services Act, and a presidential emergency under the Stafford Act or the National Emergencies Act.

The latter is what the president’s own opioid commission recommended in July. Declaring a state of national emergency would give the president even more power to waive privacy laws and Medicaid regulations.

James Hodge, a law professor at Arizona State University, said a “dual declaration” — of emergencies by both the president and the Health secretary — would give the administration more tools to fight the epidemic, but that any emergency would be a welcome response to the crisis.

Trump’s decision to go with a more measured response, a public health emergency, demonstrates the complexity of an opioid crisis that continues to grow through an ever-evolving cycle of addiction, from prescription pain pills to illegal heroin to the lethal fentanyl.

But the legal powers Trump is invoking were designed for a short-term emergencies like disasters and infectious diseases.

By law, a public health emergency can only last for 90 days, but can be renewed any number of times. There are 13 localized public health emergencies already in effect for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria and Nate, and the California wildfires.

The opioid action would be the first public health emergency with a nationwide scope since a year-long emergency to prepare for the H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 and 2010.